森野彰人

日本京都市立艺术大学美术学部教授、学部长

清水烧团地协同组合副主席

I.A.C(International Academy of Ceramics)会员

采访手记:

他既是日本京都市立艺术大学美术学部的学部长,见证了无数年轻创作者的成长;也是亚洲陶艺的前瞻者,深耕陶艺创作数十年;他就是森野彰人,2026景德镇国际陶艺双年展评委之一。

他不只是观察者,更是参与未来构建的同行者。

面对当代陶艺的跨界浪潮,面对想突破边界的青年艺术家,森野彰人的分享,道破了当代陶艺的核心——传统不是枷锁,边界不是围墙,真正的创新,永远始于自由的感知和勇敢的探索。

Q:于伶娜

A:森野彰人

Q:你如何看待景德镇国际陶艺双年展的价值?与日本美浓陶艺展有何差异?

A:现在日本的双年展、竞赛展,数量和影响力都在直线下滑,靠展览获奖成明星艺术家的路径,越来越难走。美浓展能坚持,是因为影响力聚焦美浓地区——在那获奖,能获得当地关注,从而成为艺术家。

但景德镇是世界陶瓷产业中心之一,这里的双年展奖项,含金量和影响力可能比美浓展更高,对艺术家来说,能在这获奖是件非常好的事。

Q:作为评委,你对景德镇双年展有何观察?

A:布展上,作品陈列距离可以再远些,观看效果会更好。内容上,最大特色是“中国味儿”极浓,有很多浓厚的中国传统元素,这是它和其他国际展览最不一样、也最有意思的地方。

Q:你如何看待AI等新技术介入陶艺创作?用AI创作,算作弊吗?

A:我认为数码3D打印和AI是两种不同的东西。

3D打印就像从手拉坯到电动拉坯机、再到模具,是每个时代自然出现的技术演进,只是辅助工具,不会替代创作本身。

但AI不同,它能参与思考和创作,未来大家肯定都会用——即便呼吁禁止,也会有人偷偷用。AI创作是这个时代的新产物,代表了一种积极的改变。

如果在一个展览上,同时看到AI作品和独创作品,我会平等地看待它们。我关注的不是创作媒介是AI还是人,而是作品最终呈现的整体感觉。毕竟指令背后,是个体独一无二的思考,这些思考和指令本身就是创作者核心的一部分。

重点不是AI这个工具,而是“给出指令”的人:如果你没有自己深入研究的理论基础或独特想法,你也无法给AI发出有价值的指令。

Q:对于那些非院校出身的传统工匠,想参加双年展需要做出哪些改变或调整?

A:核心在于,传统工艺和现代美术,在日本是完全不同的系统,而景德镇双年展更偏向“美术”系统。

因此,如果一个传统工匠想参与,他需要完全接受并学习一套新的系统——即美术的创作系统和评价体系。这就像以前是做中餐的,现在要从头开始学习如何做西餐——不是在原有框架上改改边角,而是要完全接受并学习进入一个全新的系统性架构。

因为这个展览的定位是面向“新”的创作。

Q:结合日本“走泥社”等现代陶艺运动的经验,对青年艺术家的创新有何建议?

A:这是个非常不简单的问题,它捆绑着特定的时代与历史语境。

日本“走泥社”的崛起并非偶然。江户末期到明治初期,日本陶瓷靠万国博览会一战成名;可1900年欧洲新设计风潮袭来,日本陶瓷瞬间失宠,只能转头向欧洲学习。直到1900年后,日本才真正把陶瓷从“产业”提升到“艺术品”的高度。

1945年后旧体系崩塌,新思想涌现,陶艺终于摆脱实用束缚,成为纯粹的造型创作,野口勇就是当时的代表。而“走泥社”成员,恰恰是把中国宋代陶瓷等传统工艺的精髓,融进了现代雕塑造型里,才走出了自己的路。

所以艺术创新的底层逻辑是懂传统,更懂时代,年轻人的创新,从不是凭空冒险,而是要读懂时代机遇,把传统的根扎深,再向新领域生长。

Q:你的艺术与教育哲学中,陶艺创作的核心是什么?

A:这是个根本问题。在我看来,艺术的本质不只是做“好看的东西”,而是去探索那些眼睛看不见、语言说不出,却能靠作品感知的存在——这才是艺术该深耕的领域。

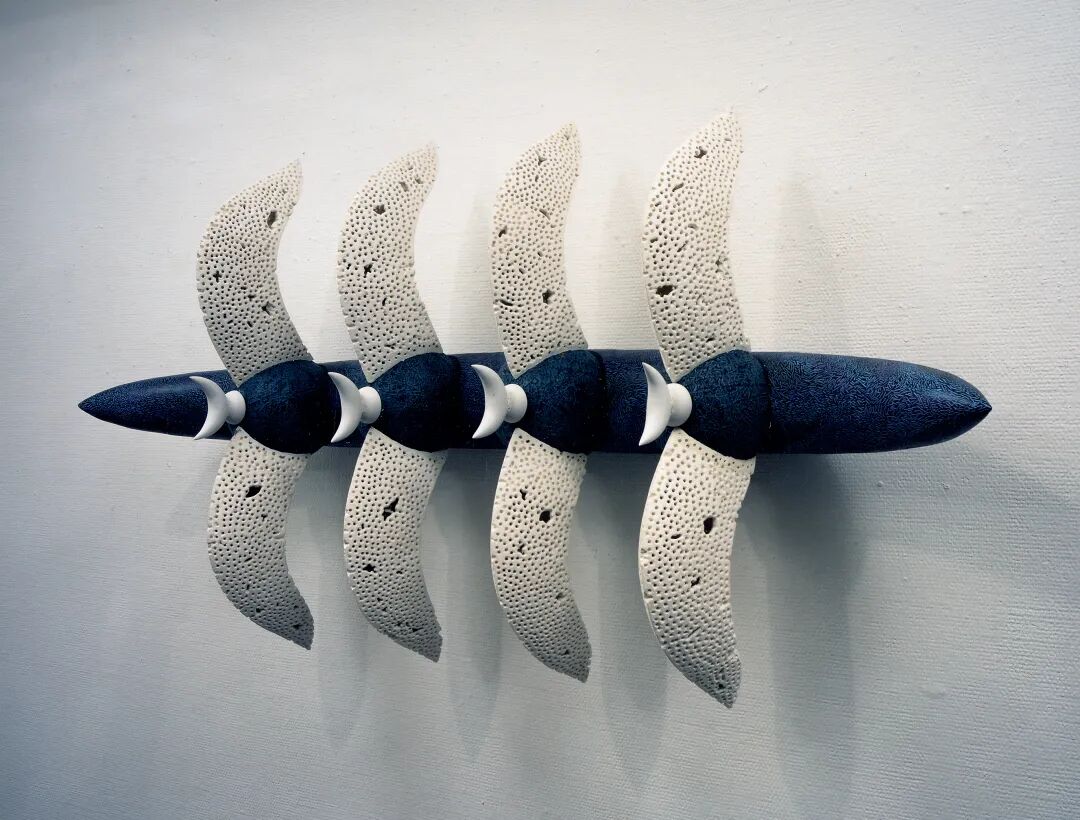

黏土的可能,远比我们想象的更宽泛:它可以是盛饭的碗,也可以是一件非实用的雕塑。我认为,创作之初别给自己设限。我自己的实践里,日用器皿、功能性器物、纯粹雕塑都有涉猎,黏土可以成为任何东西,关键是你的思想和感知要足够自由。

核心不是“黏土能做什么”,而是“你想通过黏土表达什么”。

Q:你身兼艺术家和教育家双重身份,你会如何鼓励学生走出工作室,参与景德镇双年展这样的国际平台?

A:我鼓励学生以各种形式展示自己,而不局限于某一条路径。参加国际展览、赛事是机会,在手工市集摆摊也同样珍贵。

不要被单一的风格所限制,别过早给自己“定型”——别觉得自己只能做雕塑,或只能做器物。让作品去不同的场合,遇见不同的观众,反而能更清楚自己的方向。艺术创作不是闭门造车,每一次展示和交流,都是对作品的二次打磨。

Q:2026景德镇双年展特别注重对青年艺术家的扶持,例如取消了年龄限制,并设置了“国中新锐奖”。从陶艺教育的角度来看,你认为这一平台对年轻人的独特意义是什么?

A:景德镇双年展最特别的地方,是作品分类极细——器皿、绘画、装置、雕塑等各归其类,这在很多大型展览里很少见,能让参展者更清晰地定位自己的创作方向。

对年轻人来说,这是让世界认识自己的重要机会,但意义远不止“成为明星艺术家”。更宝贵的是它提供了一个“场域”:你能亲眼看到作品被布置、被观看,听到不同文化背景的评委和观众的真实反馈。这些在工作室里永远得不到的体验,才是快速成长的关键。

景德镇双年展的独特价值不止成名,更是了解“自己的作品在他人眼中是什么”的绝佳途径。

Q:你对本届双年展的作品有什么特别的期待吗?

A:我非常期待在细致的分类中,能看到一些真正具有新概念的作品出现。特别是那些介于器物与雕塑之间、更强调“互动性”而非单纯“使用性”的作品。展览鼓励跨界艺术家也能参与进来,就是为了实现这样的多维探索。

Q:“跨界创作”也是本届双年展的一大亮点,主办方鼓励非陶瓷领域的艺术家参与双年展,你认为这种“跨界”会为陶瓷艺术带来怎样的“未来”?

A:这是个有远见的举措,直接为“瓷的未来”打开了想象力。

当画家、设计师、建筑师等不同领域的人接触黏土,材料本身的可能性会被极大拓展。更为陶瓷艺术长远的成长性和丰富性提供可能。让不同领域的人,拓展黏土的边界,就是为瓷的未来埋下更多元的种子。

Q:以评委身份写一张“致瓷的未来”的明信片,你想写给谁、写什么?

A:写给青年艺术家们:

相较于黏土陪伴人类的漫长历史,我们的分类和定义仍然狭窄。

请不要被现有框架束缚想象力。如果觉得想象力不够,就去更广阔的世界寻找养分。

本质上,黏土是“无所不能”的。它承载着过去,但更重要的,是它完全开放的未来!

英文版

Exclusive Interview | International Ceramic Scholar Akihito Morino: Crossing Boundaries and Opening Imagination for the Future

Interview Notes:

He is the Dean of the Faculty of Fine Arts at Kyoto City University of Arts in Japan, having witnessed the growth of countless young creators; he is also a forward-looking figure in Asian ceramics, deeply engaged in ceramic creation for decades. He is Akihito Morino, one of the jurors for the 2026 Jingdezhen International Ceramic Art Biennale.

He is not merely an observer, but a fellow traveler actively participating in the construction of the future.

Faced with the cross-disciplinary wave in contemporary ceramics and young artists eager to break boundaries, Morino’s insights cut to the core of contemporary ceramic art: tradition is not a shackle, boundaries are not walls, and true innovation always begins with free perception and courageous exploration.

Akihito Morino

Professor and Dean, Faculty of Fine Arts, Kyoto City University of Arts, Japan

Vice Chair, Kiyomizu-yaki Industrial Cooperative Association

Member, I.A.C. (International Academy of Ceramics)

Q:Yu Lingna

A:Akihito Morino

Q:How do you view the value of the Jingdezhen International Ceramic Art Biennale? How does it differ from the Mino Ceramic Art Exhibition in Japan?

A:In Japan today, the number and influence of biennales and competitive exhibitions are steadily declining. The path of becoming a “star artist” through winning exhibition awards is becoming increasingly difficult. The Mino Exhibition has managed to continue because its influence is concentrated in the Mino region—winning there brings strong local recognition, which can help an artist establish themselves.

Jingdezhen, however, is one of the world’s major centers of ceramic production. Awards from a biennale held here may carry greater prestige and influence than those from the Mino Exhibition. For artists, winning an award in Jingdezhen is a very positive achievement.

Q:As a juror, what are your observations about the Jingdezhen Biennale?

A:In terms of exhibition design, the distance between works could be increased to improve the viewing experience. Content-wise, its most distinctive feature is the strong “Chinese flavor.” There are many rich elements of Chinese tradition, which is precisely what sets it apart from other international exhibitions and makes it particularly interesting.

Q:How do you see the involvement of new technologies such as AI in ceramic creation? Is using AI a form of cheating?

A:I see digital 3D printing and AI as two different things.

3D printing is like the historical progression from hand-throwing to electric wheels and then to molds—it is a natural technological evolution of each era. It is merely an assisting tool and does not replace creation itself.

AI is different. It can participate in thinking and creation. In the future, everyone will inevitably use it—even if people call for bans, some will still use it secretly. AI-based creation is a new product of our era and represents a positive change.

If I see AI-generated works alongside independently created works in an exhibition, I will view them on equal terms. What I care about is not whether the medium is AI or human, but the overall impression of the final work. After all, behind every prompt is an individual’s unique thinking, and that thinking—and the prompts themselves—are a core part of the creator.

The key issue is not AI as a tool, but the person who gives the instructions. Without a solid theoretical foundation or original ideas of your own, you cannot give AI meaningful prompts.

Q:For traditional craftsmen without an academic background who wish to participate in the Biennale, what changes or adjustments are needed?

A:The core issue is that traditional craftsmanship and contemporary fine art operate within completely different systems in Japan, and the Jingdezhen Biennale leans more toward the “fine art” system.

Therefore, if a traditional craftsman wishes to participate, they must fully accept and learn an entirely new system—the creative and evaluative framework of fine art. It is like having cooked Chinese cuisine all your life and now starting from scratch to learn Western cuisine. It is not about making small adjustments within the old framework, but about fully entering and mastering a new systematic structure, because the orientation of this exhibition is toward “new” creation.

Q:Drawing on the experience of modern ceramic movements such as Japan’s Sōdeisha, what advice would you give to young artists regarding innovation?

A:This is a very complex question, bound up with specific historical and temporal contexts.

The rise of Sōdeisha in Japan was not accidental. From the late Edo period to the early Meiji era, Japanese ceramics gained international fame through world expositions. But around 1900, new European design movements emerged, and Japanese ceramics suddenly fell out of favor, forcing Japan to turn toward Europe for learning. It was only after 1900 that ceramics in Japan were truly elevated from “industry” to “art.”

After 1945, the old system collapsed and new ideas emerged. Ceramics finally broke free from utilitarian constraints and became purely sculptural. Isamu Noguchi was a representative figure of that era. Members of Sōdeisha succeeded precisely because they integrated the essence of traditional crafts—such as Chinese Song dynasty ceramics—into modern sculptural forms, forging their own path.

Thus, the underlying logic of artistic innovation is understanding tradition while also understanding one’s era. Innovation by young people is never a reckless leap into the void; it requires reading the opportunities of the times, rooting oneself deeply in tradition, and then growing into new territories.

Q:In your artistic and educational philosophy, what lies at the core of ceramic creation?

A:This is a fundamental question. In my view, the essence of art is not merely to make “beautiful objects,” but to explore those existences that cannot be seen with the eyes or articulated with language, yet can be perceived through works of art. That is the realm art should truly cultivate.

The possibilities of clay are far broader than we imagine. It can be a bowl for rice, or a non-functional sculpture. I believe that at the beginning of creation, one should not impose limitations on oneself. In my own practice, I have worked with daily-use vessels, functional objects, and pure sculpture alike. Clay can become anything—the key is that your thinking and perception remain free.

The core question is not “what can clay do,” but “what do you want to express through clay?”

Q:As both an artist and an educator, how do you encourage students to step out of the studio and participate in international platforms such as the Jingdezhen Biennale?

A:I encourage students to present themselves in many different ways, rather than limiting themselves to a single path. Participating in international exhibitions and competitions is an opportunity, but setting up a stall at a craft market can be just as valuable.

Do not let a single style confine you, and do not define yourself too early. Do not assume you can only make sculpture or only functional ware. Let your work appear in different contexts and encounter different audiences; this will actually help you clarify your own direction. Art is not created behind closed doors—every exhibition and exchange is a second refinement of the work.

Q:The 2026 Jingdezhen Biennale places special emphasis on supporting young artists, such as removing age limits and establishing the “GuozhongEmerging Artist Prize.” From the perspective of ceramic education, what is the unique significance of this platform for young people?

A:One of the most distinctive features of the Jingdezhen Biennale is its highly detailed categorization—vessels, painting, installation, sculpture, and so on are clearly separated. This is rare in many large-scale exhibitions and helps participants more clearly position their own creative direction.

For young people, it is an important opportunity to be seen by the world, but its significance goes far beyond “becoming a star artist.” More importantly, it provides a “field”: you can see how works are installed and viewed, and hear real feedback from jurors and audiences of different cultural backgrounds. These are experiences you can never gain in the studio, and they are crucial for rapid growth.

The unique value of the Jingdezhen Biennale lies not only in fame, but in helping artists understand “what their work looks like in the eyes of others.”

Q:Do you have any particular expectations for the works in this edition of the Biennale?

A:I very much look forward to seeing works with truly new concepts emerge within these refined categories—especially those that lie between vessel and sculpture, emphasizing “interaction” rather than mere “use.” The exhibition encourages cross-disciplinary artists to participate precisely to realize this kind of multidimensional exploration.

Q:“Cross-disciplinary creation” is also a major highlight of this Biennale. The organizers encourage artists from non-ceramic fields to participate. What kind of “future” do you think this cross-disciplinarity will bring to ceramic art?

A:This is a visionary initiative that directly opens up imagination for the future of porcelain.

When painters, designers, architects, and practitioners from other fields engage with clay, the possibilities of the material are greatly expanded. It also creates long-term potential for the growth and richness of ceramic art. Allowing people from different disciplines to expand the boundaries of clay is like planting more diverse seeds for the future of ceramics.

Q:If you were to write a postcard titled “To the Future of Ceramics” in your role as a juror, to whom would you write, and what would you say?

A:To young artists:

Compared to the long history of clay’s companionship with humanity, our classifications and definitions are still narrow.

Please do not let existing frameworks bind your imagination. If you feel your imagination is insufficient, go to the wider world to find nourishment.

At its core, clay is “capable of anything.” It carries the past, but more importantly, it holds an entirely open future.

(责任编辑:刘欢 审稿:兰茜 刘欢)